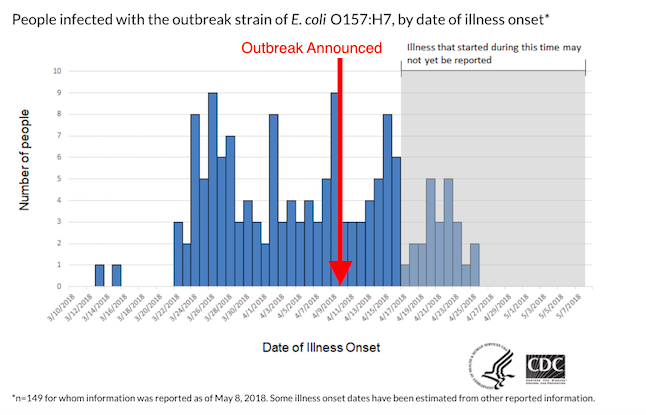

For the last month, federal health officials have been warning restaurants not to serve romaine lettuce unless they are sure that it was not grown in Yuma, Arizona. The warning stems from an E. coli outbreak that has grown to include 149 illnesses reported from 29 states. These E. coli infections are so serious that half of those sickened needed to be hospitalized, 17 are battling a life-threatening form of E. coli-related kidney failure and one person has died.

In the month since the outbreak was announced, public health officials have been short on the details of just how the public can protect its health from the dire threat these greens pose. They have not disclosed the brand names of romaine lettuce or bagged salads that may be contaminated, the names of grocery stores that may have sold these products of the names of restaurants that have served them. Restaurants named in lawsuits stemming from this outbreak include Panera and Red Lobster.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which announced a month ago that the contaminated greens were grown in Yuma, has been struggling to identify which farms in that region may be involved and what distribution channels the contaminated greens took on their journey to the nightmare scenario where people become gravely ill or die because they ate a salad.

But there are two things they have known and told consumers, retailers and restaurants for a month: the romaine was grown in Yuma, and most of the people who got sick ate it at restaurants. Why then, after a month of warnings, are people still getting sick after eating restaurant salads and other dishes containing romaine lettuce?

On May 8, the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) announced that 10 people in that state were part of the outbreak. Three of them required hospitalization and two had developed hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) a form of kidney failure that affects between 5 percent and 10 percent of E.coli patients, most of whom are young children, seniors and those with compromised immune systems.

MDH said the case-patients, who said they ate romaine at restaurants and residential facilities and at home from products they purchased at grocery stores, reported onset of illness dates ranging from April 20 to May 2. Symptoms of an E. coli infection appear between two and eight days of exposure, usually within three or four days.

If the Minnesota patient with the most recent illness, May 2, had the longest possible incubation period, he or she ate the contaminated lettuce on April 24 -14 days after the outbreak was announced and 11 days after Yuma was identified as the growing area of origin.

State and federal health officials don’t generally release specific information about the onset of illness and location of exposure, but if, as the FDA continues to state, most illnesses in this outbreak are from romaine served at restaurants, at least some of the illnesses with onset on April 21 (eight days after the Yuma announcement) resulted from restaurant meals.

“Consumers have not been told which restaurants may have been affected by this outbreak, but they should be able to trust that restaurants will get that information and act accordingly,” said Fred Pritzker, an E.coli lawyer. Pritzker, who has successfully sued restaurants in other E.coli outbreaks, is the lead lawyer with the Bad Bug Law Team at Pritzker Hageman, which is representing clients in this outbreak. To contact Fred and the other attorneys with Pritzker Hageman’s Bad Bug Law Team, Fred Pritzker, Eric Hageman, and David Coyle, use the form below.