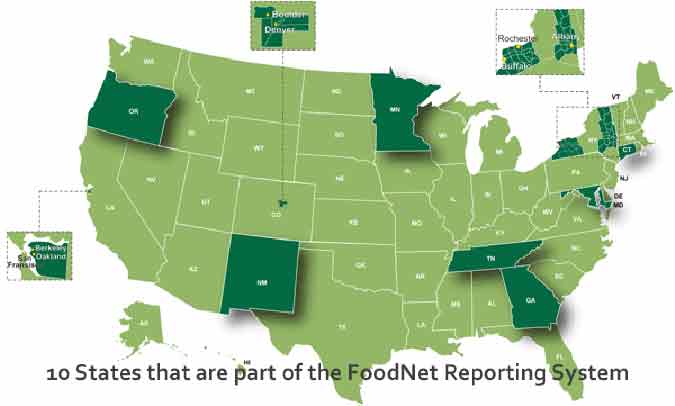

Although there has been a greater push for food safety in the last ten years, the number of people sickened by contaminated food grew in 2017, according new data from FoodNet, a collaborative program involving the CDC, FDA, USDA and 10 state health departments. FoodNet does laboratory testing of samples from patients diagnosed with infections from 9 foodborne pathogens: Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Listeria,Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia.

FoodNet works in a select surveillance area that includes 15% of the U.S. population: Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New Mexico, Oregon, Tennessee and selected counties in California, Colorado, and New York. In 2017, there were 24,484 foodborne illnesses in the FoodNet surveillance area in 2017. The CDC used these numbers to estimate an overall increase in incidences of foodborne illness in the U.S in 2017.

FoodNet attributes hospitalizations and deaths within 7 days of specimen collection to illness from that foodborne pathogen. Of the 24,484 illnesses in the FoodNet surveillance area in 2017, there were 5,677 hospitalizations and 122 deaths.

The incidence of infection in the FoodNet surveillance states per 100,000 population was as follows:

- Campylobacter (19.2);

- Salmonella (16.0);

- Shigella (4.3);

- E. coli (STEC) (4.2);

- Cryptosporidium (3.7);

- Yersinia (1.0);

- Vibrio (0.7);

- Listeria (0.3); and

- Cyclospora (0.3).

As with other years, the incidence of infections per 100,000 people was highest for Campylobacter and Salmonella.

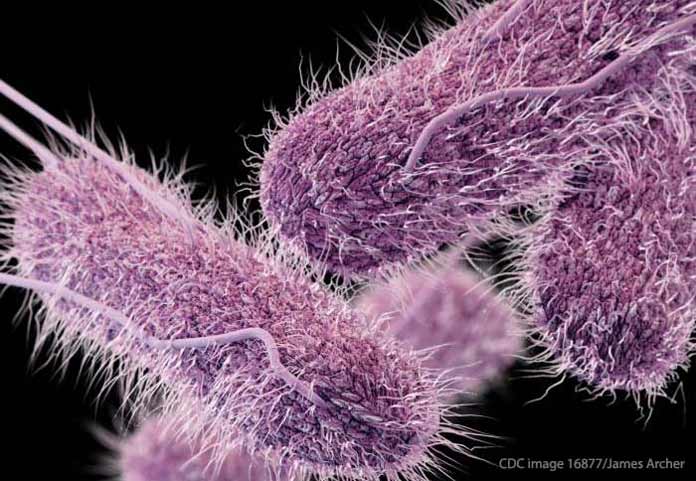

Salmonella Infections in 2017

Although the number of people sickened by Salmonella did not change significantly, there were significant changes among certain serotypes (strains):

- Infections caused by serotypes Typhimurium and Heidelberg continued to decline, resulting in overall declines of more than 40% for both since 2006;

- Infections cause by serotypes Javiana, Thompson, and Infantis all increased, resulting in overall increases of more than 50% since 2006.

Infections caused by serotypes Typhimurium (including I 4,[5],12:i:-) and Heidelberg have decreased considerably over the past 10 years. These declines mirror decreases in broiler chicken samples that yielded Salmonella and, specifically, serotype Heidelberg (USDA-FSIS, unpublished data). These declines might be partly because of industry measures to vaccinate poultry flocks against these serotypes (4) as well as implementation of measures by USDA-FSIS to decrease Salmonella in poultry and beef products. Despite these decreases, the overall incidence of Salmonella has not substantially declined since 2014–2016, partly because infections with some serotypes have increased. In particular, infections caused by serotypes Javiana, Thompson, and Infantis each increased approximately 50% compared with 2006–2008. Like most serotypes, these have been linked to both food and other exposures, including animal contact (5). Thus, some of these infections are likely attributable to nonfood exposures. USDA-FSIS also noted an increase of >50% in the percentage of broiler chicken samples that yielded Infantis from 2006 to 2017 (USDA-FSIS, unpublished data).

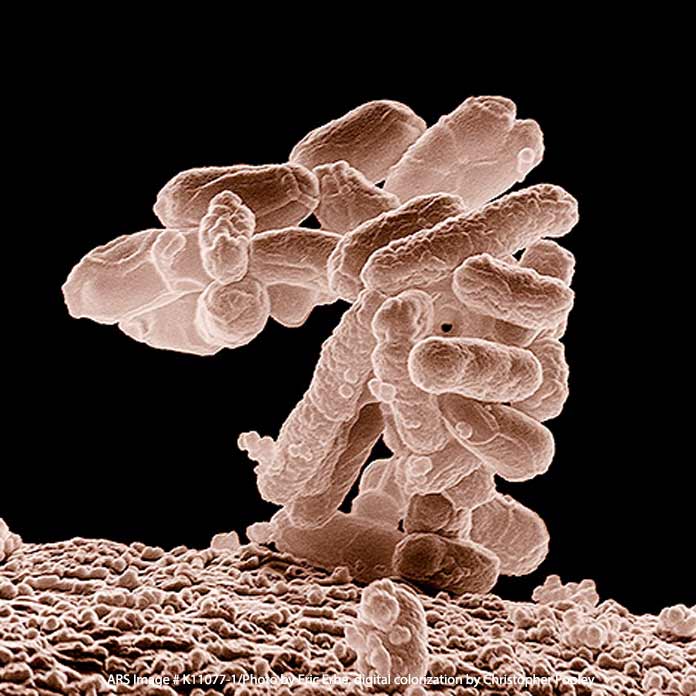

Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) Infections in 2017

Infections caused by E. coli O157 decreased about 35% from 2006 to 2016, but there was not a statistically significant change in 2017. Non-O157 strains of E. coli caused more illness in 2017, about a 25% increase from 2014. Of the 766 non-O157 E. coli isolates with serogroup determined, the most common were O26 (29%), O103 (26%), and O111 (18%).

Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) are classified by serogroup, the most common of which is O157. Clinical laboratories now commonly first determine if a specimen contains a Shiga toxin, and then test the specimen for O157. If they do not find O157, they can assume that a non-O157 STEC is present. To find out which non-O157 serogroup is present, the lab can send the specimen to a specialized laboratory. This process has provided the current data. In an outbreak of illnesses, it is used both to determine the people sickened in the outbreak and the source of the outbreak. Our food poisoning lawyers can use this information in lawsuits against restaurants, retailers and food companies responsible for outbreaks of foodborne illness.

“The rise in non-O157 STEC is concerning. We have seen a rising number of non-O157 cases involving severe illness, including kidney failure.”Attorney Fred Pritzker

The decline in E. coli O157 has resulted in a lower incidence of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) in young children. HUS is a severe complication of a Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) infection, almost always of the O157 serogroup. However, we are seeing more people develop HUS from non-O157 STEC. Most cases of HUS involve young children, many of whom suffer kidney failure and other devastating health problems. About 5% of these children do not survive.

This decline also mirrors declines in E. coli O157 in ground beef. Our law firm has been working in this area for decades, and we have seen a significant decrease in the number of E. coli O157 outbreaks linked to ground beef, or any beef product. This is evidence that food safety initiatives are working.

Attorney Fred Pritzker, National Food Safety Advocate

Attorney Fred Pritzker helps people who are sickened by contaminated food get compensation and justice. His efforts have resulted in changes to the food safety system, and some of his clients have appeared before both the U.S. House and Senate to urge the passing of food safety legislation. Fred and his Bad Bug Law Team have obtained multimillion-dollar recoveries for their clients, including a recent landmark Salmonella lawsuit that resulted in a $6.5 million verdict.

Contact Attorney Fred Pritzker

Source: “Preliminary Incidence and Trends of Infections with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food — Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2006–2017.” MMWR. March 23, 2018 / 67(11);324–328.