King County Public Health is investigating E. coli infections in three children under five. Two of the children have developed a severe complication of E. coli called hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), which causes kidney failure.

Illnesses were reported to health officials on May 26, June 1 and June 6. It is too early in the investigation to know if the cases are related. Testing is being done on E. coli isolates to determine if they are a genetic match.

Symptoms of illness include bloody diarrhea and abdominal cramps. The pain associated with these symptoms is severe.

How Does E. coli Cause Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome in Children?

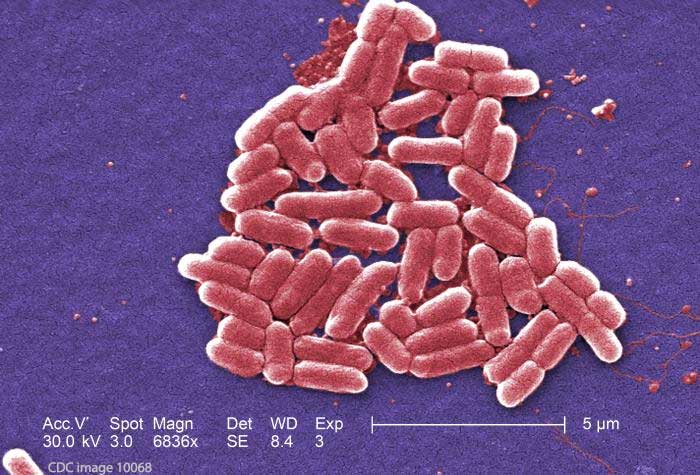

If a child ingests E. coli, the bacteria can cling to the lining of the colon and produce Shiga toxins. This kind of E. coli (some strains are not dangerous) is Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli, often referred to as STEC by health officials.

The Shiga toxins can get into the blood and travel to the kidneys, where they can destroy red blood cells, thereby:

- reducing the number of red blood cells, causing anemia; and

- causing tiny blood clots (thrombi) to form in the filtering system, preventing normal renal function.

Children with E. coli-HUS can suffer kidney failure, which can then lead to multiple organ failure and death.

Vehicles of contamination include:

- contaminated food or water;

- contact with feces of animal that is infected;

- contact with feces of a person who is infected.

It takes only a few cells to make a child sick. This means one bite of contaminated hamburger, for example, can tragically change a child’s life.

What is an “Outbreak” and How is it Investigated?

An outbreak happens when 2 or more people with confirmed pathogenic infections are sickened by the same source.

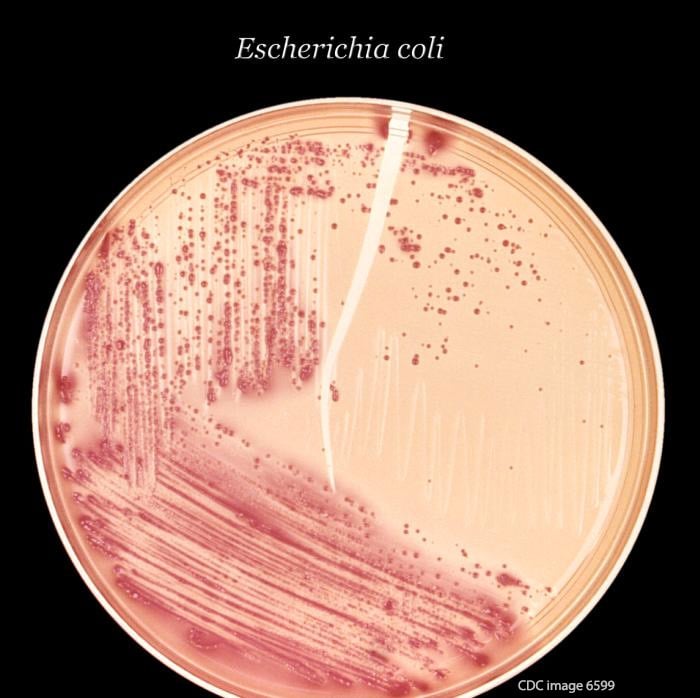

To find cases in an outbreak of E. coli infections, stool samples are tested. If the bacteria is found, E. coli isolates (isolated cells) are sent to public health laboratories (generally run by the CDC), where a kind of “DNA fingerprinting” called pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is done. Investigators determine whether the “DNA fingerprint” pattern of E. coli bacteria from one person is the same as that from other people. Bacteria with the same “DNA fingerprint” are likely to come from the same source, according to the CDC.

To find the source, health officials interview the parents of children sickened to find out where they went and what they ate in the days before onset of illness. They then look for E. coli with the same DNA fingerprint in samples of food, water, animal feces (if the children visited a petting zoo), and environmental samples from restaurants, daycare centers, etc.

It can take weeks to confirm that 2 or more people were sickened by the same source, and much longer to find the source.