Officials at St. Joseph’s Health Center in Syracuse, New York, have revealed that earlier this year, in March 2015, another patient contracted Legionnaires’ disease at the hospital and subsequently died. St. Joseph’s is currently under scrutiny for its failure to disclose 3 Legionnaires’ disease cases. It was these cases that prompted a recent inspection of hospital water systems and testing for potentially fatal Legionella, the bacteria that causes Legionnaires’ disease, a severe type of pneumonia.

According to local Syracuse news sources, the hospital stated that, while the patient did in fact contract Legionnaires’ disease while in the hospital, this patient “died of other causes.” Hospital personnel traced the bacteria to a radiology department sink, which they disinfected and which then tested negative for Legionella.

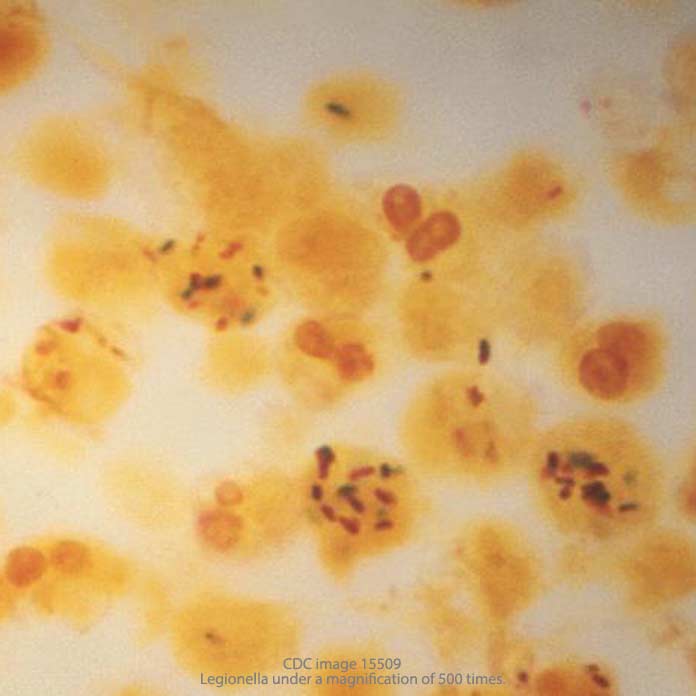

Legionella bacteria is ubiquitous in the environment – it occurs in lakes, rivers, and even in potting soil. Most healthy people are not sickened by exposure to the bacteria, but those with suppressed immune systems and underlying medical conditions are highly susceptible. And when an immune-compromised patient contracts Legionnaires’ Disease in a hospital, he or she has a 50% chance of dying.

Both ethical and legal issues arise from St. Joseph’s failure to publically disclose the patient fatality in March. Since the patient contracted Legionnaires’ disease on hospital grounds, it is begging the question to say that Legionnaires’ Disease “was not the cause of death” – we must ask whether it was a contributing factor to that death.

The question also arises as to why, after a fatal Legionnaires’ disease infection occurred at the hospital in March, water systems were not more closely monitored for regrowth of the Legionella bacteria – especially in a New York state public hospital. New York, Maryland, and Pennsylvania are the only states thus far where health departments have issued comprehensive guidelines for containing the risk of Legionella contamination in hospitals. The New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) first released its guidance in 1999, updating this document ten years ago in 2005. The latest version specifically states:

“If a case of Legionnaires’ disease is definitively linked to a healthcare facility, the implicated systems must be disinfected/treated immediately. Complete eradication of Legionella is not feasible and re-growth will occur. Therefore, long-term control measures must be implemented. Environmental surveillance (collecting water samples or plumbing system swab samples for Legionella analysis) is necessary to ensure that disinfection and long-term control measures are effective.”

The diagnosis of a hospital-acquired case of Legionnaires’ disease should have alerted officials at St. Joseph’s to the need to monitor its water systems for signs of bacteria regrowth. Obviously, it did not. Six months later, the Legionella was back in the hospital’s new $63 million, “green” Christina M. Nappi Surgical Tower, a 104,000 sq. ft. facility that primarily serves cardiac patients. Current evidence suggests that the growth of the bacteria was enabled by the state-of-the-art facility’s new “low-flow” water faucets, which allow water to collect, stagnate, and recolonize the potentially fatal Legionella bacteria.

Separate, repeated instances of Legionnaires’ disease in a medical facility within a twelve-month period raise a red flag regarding the adequacy of that hospital’s disease prevention and sanitation programs. At some point, legal action becomes the most effective way not only to secure the damages owed to victims of hospital-acquired LD, but also to provide a strong incentive to the hospital to better safeguard its water systems in the future.