Following the recent outbreak of Legionnaires’ Disease cases at St. Joseph’s Health Center in Syracuse, NY, New York Senator Charles Schumer (D) has issued a call for the implementation of national standards requiring testing of hospital water supplies and water systems in large public buildings.

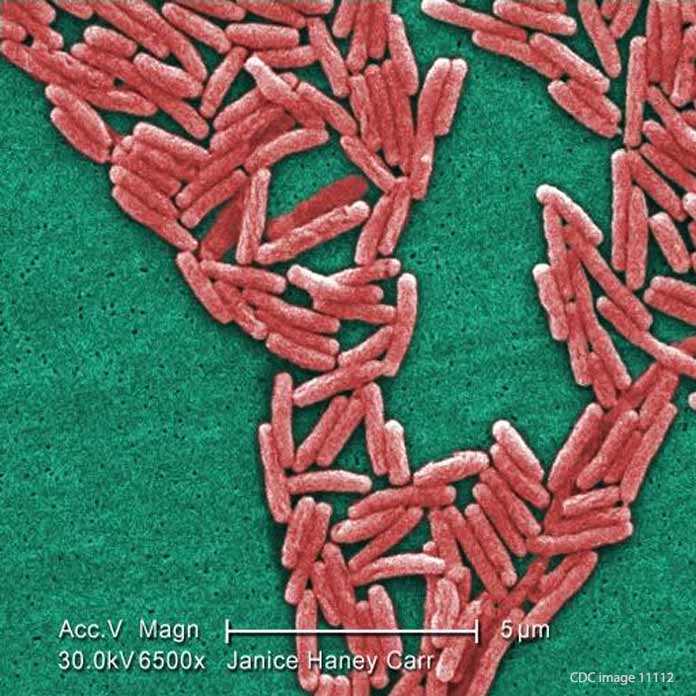

St. Joseph’s hospital officials have confirmed today (11/3/2015) that follow-up testing of its water systems has definitively isolated the threatening Legionella pneumonia bacteria in an ice machine and in two patient sinks equipped with water-saving “low-flow” faucets. There have been 3 cases of Legionnaires’ Disease associated with the hospital; two patients are confirmed to have contracted the disease in the facility, but the hospital maintains that it is “unclear” whether the third patient, who died at the facility, was infected at St. Joseph’s or elsewhere.

Schumer’s request for federal regulation of Legionnaires’ Disease testing is both admirable and warranted, but it is hardly original; hospitals have long known of the dangers that contaminated water systems might pose to patients made highly vulnerable by pre-existing medical conditions such as respiratory illness, diabetes, cancer, coronary disease, HIV, and other immuno-suppressive diseases. Moreover, independent industry standards have been defined and revised for the past two decades.

Scientists began alerting hospital personnel to the risks posed by Legionella-contaminated water systems in the 1990s, researching and publishing hundreds of peer-reviewed articles that have established gold standards for Legionnaires’ Disease prevention.

One of the groups that heard and responded to researchers’ recommendations for preventive Legionella testing was the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), an international 55,000-member engineering society headquartered in Atlanta. As early as 2000, ASHRAE published guidelines to minimize risk in hospital plumbing systems; more recently, ASHRAE’s Standards Committee labored for six years to define standardized and enforceable rules for the control of the Legionella bacteria in plumbing systems, soliciting advice from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A definitive set of guidelines was published in 2015.

A bare handful of state health departments (New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland) and municipal hospital systems have either adopted ASHRAE’s preventive testing standards or have developed their own guidelines in an attempt to heighten vigilance and testing past the standards suggested by the CDC. In 2005, the State of New York Department of Health issued extensive guidelines to hospital administrators emphasizing the danger posed by the Legionella bacteria and outlining preventive measures to be taken to protect immune-compromised patient populations:

“Cases of Legionnaires’ disease result from exposure to contaminated water aerosols or aspirating contaminated water. A link has been established between Legionnaires’ disease and potable water or aerosol-generating devices, such as cooling towers, showers, faucets, hot tubs, whirlpool spas, respiratory therapy equipment (e.g., nebulizers) and room-air humidifiers. Immunocompromised patients at healthcare facilities are at greater risk of infection. Therefore, cooling towers, hot water systems, and other equipment that may generate aerosols must be properly operated and maintained … Complete eradication of Legionella is not feasible and re-growth will occur. Therefore, long-term control measures must be implemented. Environmental surveillance (collecting water samples or plumbing system swab samples for Legionella analysis) is necessary to ensure that disinfection and long-term control measures are effective.”

Most tellingly, the Joint Commission, responsible for hospital accreditation, began incorporating provisions regarding preventive water system maintenance and LD testing protocols in its accreditation standards as early as 2009 (Revised Standard EC.02.05.01), listing as one of its “elements of performance” that the hospital under review “minimizes pathogenic biological agents in cooling towers, domestic hot-and cold-water systems, and other aerosolizing water systems.”

Thus, although we do not yet have a single, federally-mandated standard for Legionnaires’ Disease testing, hospital systems have long been cognizant of the vital need to provide preventive maintenance and testing of their plumbing systems for potentially fatal pathogens like the Legionella bacteria.

When they fail to do this, people die – up to 50% of Legionnaires’ Disease cases in immune-compromised individuals (the very people who need to go to the hospital in the first place) are fatal.