2 patients were sickened by the Legionella bacteria last month (mid-September 2015) at Rhode Island Hospital, the same facility responsible for two earlier community-transmitted cases of water-borne Legionnaires’ Disease in November 2014. After last year’s autumn breakout, it was reported by the Providence Journal that hospital officials intended to “superheat” and flush the water supply in all affected areas. However, in January 2014, a patient at nearby Miriam Hospital , co-founder with Rhode Island Hospital of Lifespan Health Systems, also contracted Legionnaire’s Disease. In this most recent September incident, Rhode Island Hospital has repeated its intention, in a statement to NBC 10 news, to “implement a comprehensive water treatment plan that will include “superheating and flushing” the water supply in the potentially affected building.”

In a similar case of hospital-transmitted Legionnaire’s Disease (legionellosis) reported by NBC 10, an elderly woman died after contracting LD in May 2015 at Kent Hospital in Warwick, RI. Although she tested negative for the bacteria upon initially being admitted to the hospital, she tested positive 10 days later. Legionella bacteria were subsequently identified in 4 of the hospital’s 24 ice machines. Dr. James McDonald, of the Rhode Island Department of Health, also confirmed that there was a second “possible case” in the same time frame of a patient who was discharged, then returned to Kent Hospital after two days and was tested positive for the Legionella bacteria. However, because this patient was not in the hospital for 10 contiguous nights prior to the diagnosis, he claimed that this “possible case” did not meet the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)’s criteria for a hospital-acquired infection. Thus, the Rhode Island Department of Health says that it does not consider the Kent instances to be an official “outbreak.”

Rhode Island Hospital Legionnaires’ Disease Research

It isn’t unprecedented for hospitals to play fast-and-loose with their processes of Legionnaires’ Disease identification and outbreak reporting. In part this is because of unclear standards governing who should be tested for the disease and who should not.

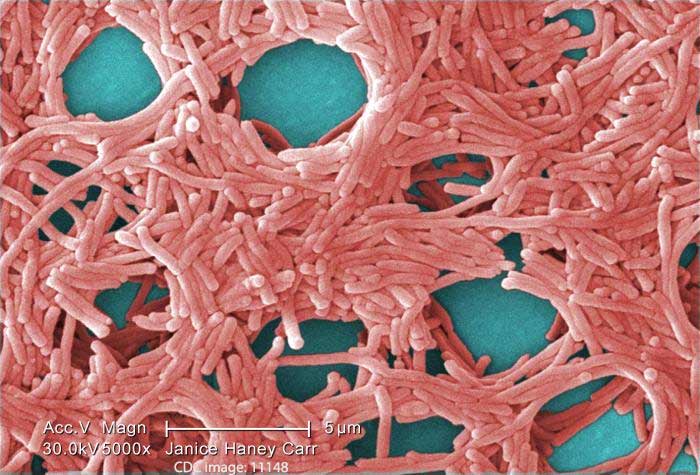

In a telling 2011 study, “How often is a work-up for Legionella pursued in patients with pneumonia? A retrospective study” (BMC Infectious Diseases 2011, 11:237 doi:10.`186/1471-2334-11-237), Rhode Island Hospital researcher Dr. Leonard Mermel, Medical Director of the Epidemiology and Infection Control Department, and co-authors Brian Hollenbeck and Irene Dupont concluded that when Rhode Island Hospital tested pneumonia patients for the Legionella bacteria between 2005 and 2009 based upon standards set for community-acquired pneumonia by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS),

“A diagnostic work-up for Legionella (i.e., urine antigen testing or culture of respiratory specimens) is performed in less than half of patients with pneumonia in our endemic region. If Legionella testing was curtailed to those recommended in the IDSA/ATS community-acquired pneumonia guidelines, the diagnosis of Legionella pneumonia would have been missed in 41% of our cases. Thus, Legionella pneumonia may be underdiagnosed and more widespread. Legionella testing should be considered to better delineate the choice and duration of antimicrobial therapy and to assist in uncovering clusters of Legionella in the community or healthcare setting.”

According to this study, the IDSA-ATS suggests that Legionella pneumophila urine antigen testing is only recommended for patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) or with failure of outpatient antibiotics, active alcohol abuse, history of travel within the previous two weeks, or pleural effusion (excess fluid build-up around the lungs). They do not establish a solid groundwork for identifying potentially hospital-acquired Legionnaire’s Disease.

Are Hospitals Liable for Legionnaires’ Disease?

Indeed they are. If the source of Legionnaires’ Disease was a contaminated water system at a hospital facility or if medical personnel failed to diagnose Legionnaires’ Disease resulting in severe illness or death, you can sue for damages including medical expenses, lost wages, disability, pain, emotional suffering, and other lawful damages; victims’ families have the right to sue for loss of care and companionship, funeral expenses, and lost income to the family.

Most Legionnaires’ victims who contract the disease in hospital settings already have compromised immune systems; they are most likely to be elderly, smokers, cancer and transplant patients, patients with chronic lung disease, or patients on high-dose steroid therapy. It is thus contingent upon hospitals and healthcare systems to ensure the safety of the environmental water systems to which these susceptible patients are exposed.

If you or a loved one has contracted Legionella pneumonia within a hospital setting, please contact Fred Pritzker at 1-888-377-8900 or use our free online consultation form.